The Birth Of Entertainment

Brinck Slattery • Jan 17 2018

The arts have always been a difficult business. In the 1600s, the arts were so competitive that poets and producers hired professional applauders called claques. Shakespeare's plays have literally caused riots. Managing fans and haters have always been a challenge, and our modern mass media culture has been forged in the birth and death of a thousand fandoms.

While fan culture seems to be an enduring part of the human experience, the production of art and entertainment has radically changed since we started scribbling on cave walls. It's easy to assume that things have always been the way they are, but people in the past approached entertainment in a very different way than we do today.

Art and Entertainment In Ye Olden Times Of Yore

People have been making art for about 27,000 years, for the same reasons they do today - to transcend time and space by leaving their mark on the world, to express their individuality and humanity, and to impress potential romantic partners. But unless they were making jewelry, carving tombs, or weaving bespoke loincloths for the local chief, there weren't any professional artists, and other than telling stories by the fireside, there wasn't any "entertainment" in the modern sense.

Greece (The Musical)

The first public performances popped up in ancient Athens, and the cost of these productions led to the first known patronage relationships in the arts. The theater was important to the Athenians, and they had enough wealthy merchants committed to the theater that they could afford to put on serious shows. Every spring at a feast called the Dionysia; playwrights would compete for the favor of the city in what was basically an ancient Sundance.

One wealthy Athenian was named the Choregos each year and made responsible for producing the winning play. That included paying for costumes, a director, scenery, props, musicians and actors (except for the flute player and non-chorus actors, who were provided by the state for arcane reasons). And just like today, entertainment was an expensive pursuit - some productions cost ten times as much as a skilled worker earned in a year.

This arrangement created the works of Sophocles, Aeschylus, Euripides, and several other brilliant playwrights who you've also forgotten about since college.

Middle Age Crisis

Time passed. In Europe, lots of art was created, mostly in royal courts or churches, where monks created beautiful illuminated manuscripts and lords commissioned impressive architecture. The situation was similar in Asia - artisans, poets, and dramatists created a lot of art, generally funded by and under the direction of the highest political authority in the region.

In hindsight, it was a productive period for the arts; but at the time, entertainment options were few and far between for regular people. Traveling musicians and entertainers were the occasional break in a bleak, terrible period in history.

Gleeman (in England), Troubadours (in Western Europe) and their equivalents in almost every culture worldwide would sing, dance, play instruments, tell stories, and do tricks for a fee or lodging - a sort of medieval one-man variety show. Troubadours even had some titillating psycho-sexual mysticism thrown into their repertoire for good measure.

Renaissance Persons

Fast forward to the Renaissance - after years of trickling from the countryside to the cities; there were enough people in urban spaces to support ongoing theatre companies, orchestras, and operas. In Italy, impresarios took on the cultural (and financial) responsibility of organizing and funding operas where they charged for admission.

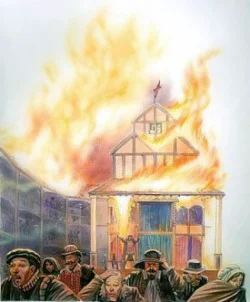

In 1599, Shakespeare's theater company (the Lord Chamberlain's Men) built the Globe Theater, an employee-owned enterprise that produced Shakespeare's plays. Artists turned into businessmen, and they did a good job of it. The Globe made enough money to survive for decades and was even rebuilt after it caught on fire when a stage cannon backfired.

The Renaissance was a literal rebirth for entertainment. Entertainment became "what people are willing to pay money to see" instead of "a thing which makes the king laugh" or "a production that displays appropriate solemnity and moral attitudes for the Bishop." This happened at the same time that the novel was becoming a thing (a hated thing that authorities believed would irreparably damage women's minds and drive people mad). Widespread use of the printing press made it possible for writers to make enough copies of their work to distribute it widely.

In a new way, people were able to seek out other people who created art they enjoyed and then pay them for it.

As we know, this didn't lead to a DIY opera industry or the disappearance of productions funded largely by a single patron. The technology didn't exist for artists to connect with their entire audience and distribute their creations. Unless they were extraordinarily wealthy, a fan couldn't experience a creator's art unless they were already in the same area. And if they lived in different areas, it's likely the fan would never have heard of the creator in the first place.

Artists had to find a hybrid system, and straddle the line between finding supporters that they'd have to please (governments, religious officials, wealthy businessmen, etc.) and supporters who just want to get more of the artist's work but didn't necessarily have deep pockets.

The creative world stayed in this limbo until the introduction of commercial radio and ad-supported content, which you can read more about in this post.