The DMCA's Chilling Effect on Security Research and Innovation

Jack Robison • Jan 14 2016

You walk into a Barnes and Noble, pick up a copy of Look Me in the Eye, hand the cashier money, and leave the store. The book now belongs to you, right? Of course, it does. You are free to write notes in the margins, sell it second-hand to a friend, or even rip it up if you felt so inclined. What you can't do is copy portions of it and claim them as your own work; you own your copy of the book, but not the copyright.

This is pretty straightforward and doesn't violate most people's understanding of copyright and ownership. But let's say you skipped the Barnes and Noble and instead went to Walmart to buy a Sony PS3. Is it any different? Actually it is.

When the PS3 was released, many tech enthusiasts were eager to buy such a powerful computer for such a low price, despite it masquerading as a gaming machine. They would install Linux on their PS3 and use it as a desktop computer. To their dismay, Sony responded with lawsuits claiming copyright violation. Under the Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA), corporations have gained sweeping powers to effectively retain ownership even after the item has been sold. Apple has given the same treatment to iPhone owners who have had the audacity to try to install software that Apple hasn't personally signed off on, i.e. iPhone owners who "jailbreak" their phones.

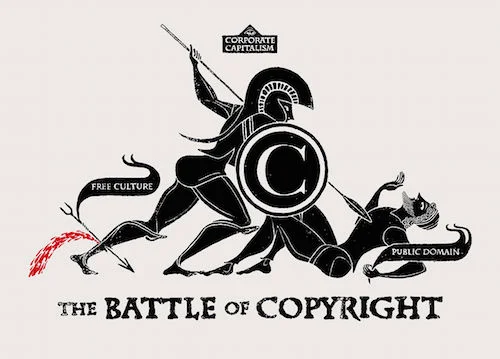

Copyright has gone far beyond its original intent and beyond how most people understand it to work. Instead of being used to prevent copying, it is now also used to prevent modification – even if there is no commercial angle to the modification and the only purpose is better satisfying the desires of the owner. Maybe taking notes in the margin of your favorite book isn't so clearly legal after all; the fact that such an argument could be made demonstrates the ridiculousness of the DMCA and how it hurts customers.

Auto manufacturers have exploited the you-own-what-you-buy-except-for-when-we-don't-like-how-you-use-it DMCA too. Want to reprogram your car's engine control unit? You might be violating the DMCA. Really, any work done on the electronics in a car risks violating the DMCA. This exposed tinkerers and independent shops alike to a tremendous risk, leaving official dealerships as the only safe route for these repairs. But fret not, all of that changed this past fall. In a first, the government has issued an exception to the DMCA to explicitly allow tinkering with automotive electronics and software.

So what pushed the government to do this? In large part, it was the recent Volkswagen scandal. The Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF) argued that the DMCA had prevented independent shops and tinkerers from testing and identifying VW's deception for years – and the government listened. That said, it's a real shame that it takes a very public deception being uncovered to change the law. And it raises the question – how much deception, negligence, and incompetence is still being covered up in all of the areas without a DMCA exemption? Don't expect an answer, because as the EFF has pointed out, the DMCA has a chilling effect on security research.

Researchers of both the academic and DIY types steer clear of looking for such problems, because by finding them they may violate the DMCA and come under legal pressure. That means the only major efforts to root out security vulnerabilities and misrepresentations are under the table, and the hackers doing such work don't tend to have the good of the public in mind.

The new DMCA exemption is a great start, but in the grand scheme, it is a mere baby step. The DMCA prevents you from having products you can trust. It is also quite telling of how corporations view their customers when they pursue unpaid volunteers trying to fix product mistakes. You'd think they'd be happy such people are out there. To be sure, some corporations appreciate these types of customers – but the good guys don't have the same lobbying power. That's because DMCA supporters view their customers as their own assets, as subjects who are only allowed to play with the toys they've bought within the officially sanctioned sandbox. I hope the trend reverses, but to get there, we're going to need to expose deception, negligence, or the more benign incompetence in far more areas than the automotive industry alone.